Lani Barry

History of Make Up

Professor Hewitt

Classic Beauty: The History of Makeup

Gabriela Hernandez, a professional makeup artist and historian has compiled a vibrant and informative illustrated history of makeup. Covering a variety of topics, she begins with the origin of cosmetics, and moves on to ‘cosmetics in antiquity’. There are also separate sections dedicated to the history of adornment to the eyes, the lips, and the face. Beginning in the 1920’s, and carrying on to the media generation of the 2000’s, Hernandez devotes sections to the makeup history and trends of each decade. Finally, she concludes the book with her thoughts on beauty and leaves a glossary of terms for the reader. With a collection of cinematic stills, diagrams, and samples of makeup products, her book is a visual treat to read.

When you begin, the introduction decrees ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, and that the book is a compilation of history’s perspective evolving over time. She makes sure to include political, economic, and social explanations for why cosmetics came into fashion (or why they fell out of fashion), and equally what new ideas were birthed with the developments of makeup formulas and tools. What is especially helpful is the timeline she included in the early chapters, displaying time periods in which particular civilizations made discoveries on grooming tools, body adornment, and bathing practices.

The beginning chapters on early history cover a few thousand years of progress. First the prehistoric ‘Venus’ statues are introduced, with Paleolithic ideas of beauty in fertility in a larger woman. It is also around this time when the cave paintings depicting body adornment show that early man must have used similar varieties of mineral pigments and grease to decorate. Along with body paint, creation of tools did not exclude grooming devices, and varieties of scissors and razors have been found from as early as the Bronze Age.

Found artifacts such, as mirrors and other objects of adornment, suggest that preoccupation with appearance has been present at all periods throughout history. (Hernandez, 14)

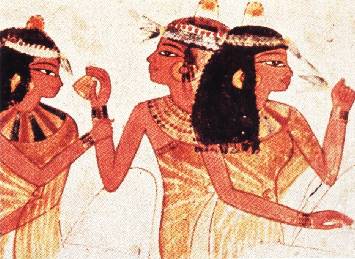

Continuing with ‘Cosmetics in Antiquity’, the sections on Ancient Egypt are full of historical information. Egyptians used a full spectrum of facial paints for decoration, most commonly red ochre, green malachite, and black kohl – which appears in every quintessential depiction of Egyptians and thick eyeliner. Along with makeup, they used a variety of perfumes and scents to adorn the body, but also protect the skin from the sun and insects. Egyptian razors, pumice stones for depilation, and sand exfoliation scrub have all been found in archeological digs, and described on ancient papyrus.

Ancient Mesopotamia developed similar cosmetic uses, also including the use of styling tools for curling hair (and beards) and hair styling products such as oil, resin, and wax. They were also one of the first civilizations to concoct hair dye from extract of leek and cassia. Unlike the Egyptians who creative ornamental jars and containers for their toiletries, remains of Mesopotamian civilizations show makeup pigments saved in shells.

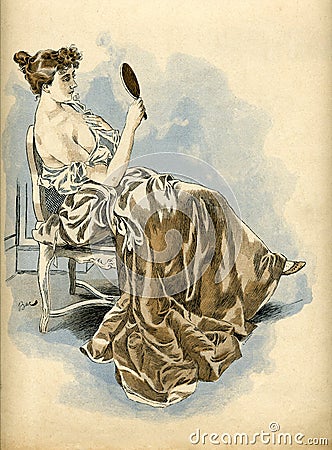

Artwork in the form of vases and statues of the Ancient Greeks seem to display a more classic woman, adorned with less paint than their Egyptian or Mesopotamian counterparts. Natural beauty was prized over an overly made-up woman; writings of ancient Greek men disdainfully describe the cosmetic practices of Greek women. However, perfume, hair removing devices, rogue, elaborate hairstyles of curls, and the use of mirrors were known to Ancient Greek women, therefore appearance was still regarded as important.

Women of Rome borrowed cosmetic practices from Greece and Persia, including the darkening of eyes and brows or concocting perfumes and scents. Early use of cosmetic creams began, scented water and perfumes were prized, and Roman women began to powder their faces. Like the Greeks they used rogue, but began to create variety in shades of pinks and reds. Rogue was not just for the cheeks but for the lips as well, and to contrast the blush of youthful lips and cheeks, a concoction of vinegar with either white lead or chalk was applied to the face to pale the complexion. Beauty was serious business to the women of Rome; enough that more affluent women would enlist the help of beauty professionals.

Wealthy Roman women enlisted cosmetic artists and hair stylist to help with their beauty regimen. The cosmetic artist was called the cosmatae, and the mistress of the toilette, the ornatrix. (22)

The middle ages saw a lack in education, trade, and health practices until the Renaissance. There is little information on the cosmetic practices of the medieval era, except for Viking appreciation for tattoos and jewelry, and that the early Roman Catholic Church disregarded beauty adornment as vanity. The use of soaps, perfumes and scented water, mirrors, hair dye, and face paint gradually reappeared in the early 16th century. Hernandez writes that blonde or auburn hair became the fashionable color for women during the time of Queen Elizabeth the first (there is speculation that the ruling Popes preferred blondes), and during this time the use of cosmetics became more acceptable. Wealthy women matted their complexion with white ceruse powder, used rogue, dyed their hair, and preferred musky scents.

Puritans did not approve of any adornment, that the use of anything other than soap was sinful and the work of the devil. Despite the ties of vanity and witchcraft, Puritan women still followed the fashion of a broad forehead and plucked their hairline and eyebrows out.

Cosmetics and makeup saw an increase in use and development in the 1700’s. Scents and smelling boxes, astringents, creams, makeup in the form of crayons, and practices of dental hygiene were acceptable to use by the wealthy classes. Royal courts were known for their extravagant hairstyles and made up courtiers, Marie Antoinette herself held a ‘public toilette’, where she’d keep company and hold conversations during her beauty regiments.

Like the Romans, a pale complexion with darkened eyebrows, rouged lips and cheeks were the beauty ideal of the 1700’s. Despite the toxic properties of lead (which was known even to the Romans), the use of lead-based facial powder was continually used, even permanently damaging the faces of individuals who used it for prolonged periods of time. The disdain for extravagance and elaborate cosmetic use returned during the French revolution, and the American colonists mocked the elaborate grooming practices of the British, using terms as ‘dandy’ or ‘macaroni’ to label a lavish dresser.

While the attainment of idyllic ‘natural beauty’ carried on into the 1800’s, toilettes further expanded with a variety of homemade concoctions, or products that began to appear on the market. Guidebooks and instruction pamphlets were published to educate women on beauty practices, and the importance of keeping up a good appearance. The overt use of paint or beautification held negative connotations, but the public demand for cosmetics only further expanded.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 held in Hyde Park, London, England, showcased rich displays of cosmetics, soaps, and fancy toiletries and created a high demand for items associated with grooming. (42)

Rogues, powders, creams, and toilette waters were advertised with catchy slogans and packaged in intriguing designs. What was once a homemade commodity, beauty regiments passed down through generations of women, the ideal face was now available in jars and boxes at druggists, stores, and salons opened by beauty entrepreneurs.

Public appearance or application of makeup remained morally questionable, until a generation of girls came of age in the 1920s. Empowered by the passing of women’s Suffrage, everything changed as the cloaks of feminine oppression were thrown off, and an appreciation for an independent modern woman took its place. Hemlines were shortened, haircuts were bobbed, cigarettes were smoked, and working women began to form their own autonomous identity. Face powder was kept on hand in ornate compacts and applied in public, Hollywood helped push the use of wax mascara, lipstick came in a twist-up tube and in a variety of colors, eye shadow was acceptable off the silver screen. The large eyes, thin eyebrows, and finger waves of the flapper girl were all the rage, and attainment of youth and beauty was no longer immoral as women began to spend more of their wages on cosmetics and fashion.

The 1920s marked the beginning of the pursuit of youth. Mature women were never again seen to be truly fashionable. Women strived to look young, for youth was now synonymous with beauty. (94)

Hernandez completed her chapter on the 1920s with a color palette of makeup shades seen during this time, and a breakdown of how a makeup artist, like Max Factor, would apply screen makeup to a film actress. Beauty icons such as Clara Bow, Josephine Baker, Louise Brooks, along with antique compacts and photos of surviving makeup samples (such as Max Factor’s cream foundation) are shown at the chapter’s end.

Despite the depression and the developments of World War Two in Europe, the 1930s continued to look to the cinema for beauty idols and fashion trends. Cosmetic availability continues to expand, and women have the option to purchase sets of facial cleansers, creams, popular perfume scents, makeup, and nail lacquer. With the introduction of color into films, the composition of makeup evolves to resemble a more realistic skin tone than ever before. The over-application of eye makeup of the flapper evolves into a polished look of lipstick, penciled-in thin eyebrows, and looser hairstyles. The use of rouge declines, but when used a cream-paste formula is preferred over powder form. Henna or mascara darkens the lashes and separates them, but does not lengthen or add volume at this time. Film actresses such as Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, and Marlene Dietrich introduce the use and popularity of false eyelashes to the public.

The introduction of color motion pictures makes a huge impact on cosmetic sales. Women imitate the shape of the lips or eyebrows and the exact cosmetic colors seen on actresses. (107)

Photographic samples of early Maybelline Mascara, Princess Pat and Heather theatrical rouge, and Plough’s Cleansing Cream are all shown in decorative metal tins, along with a patent of Alexandre Gimonet’s invention for ridged metal tip mascara applicators. Beauty ads in magazines are now seen in full-color by the end of the 1930’s, promising love and beauty to the consumer with the purchase of a product line.

During the Second World War, rationing of supplied affected the quality and quantity of cosmetics. Despite the decline in availability of products, and a large number of women in the workforce, makeup use did not curb and Hollywood continued to lead the trends of beauty. Elaborate hairstyles of wavy hair, victory rolls, and up-dos replaced the statements of splendor and femininity a dress once did. The face was simply powdered, brows penciled, and a tube of red lipstick became iconic of wartime spirits and triumph for women.

The use of bright red lipstick has such an impact on morale for women during World War II that it has become forever linked to improving confidence and as a symbol of victory. (119)

Over pronounced lips were fashionable, and the use of rouge was kept high on the cheekbones and blended in to achieve a more natural look. Eyebrows were tweezed and penciled to arch, along with heavily applied mascara to the outer corners of the eye. Eyeliner was no longer applied daily, and eye shadow colors were kept to natural tones

After the war the cosmetic market bounced back and makeup was now available in more variety of colors and formulas than ever before. The 1950’s saw the introduction of products like waterproof mascara, liquid eyeliner, and eyelash curlers. Before the nation had needed a strong American woman, but the return to femininity was pushed by society as women were supposed to return home, marry, and start a family. Women were expected to wear makeup and keep up their appearance, as they were expected to maintain their home and family.

Technology had progressed to developing new home appliances, cars, airplanes, synthetic textiles and materials like plastic. A major influence on beauty trends was no longer film, but television. Models on TV advertisements now promoted a variety of products and makeup trends, and the achievement of subdued sexuality and sophistication was fed to women through marketing campaigns of the early 1950’s.

‘Modern’ makeup came in a variety of colors but shades of purple, blue, and frosty metallics became the most popular. Despite the importance the 1950’s woman placed on her visit to the hairdresser, home hair treatments and dye, along with curlers and hairpieces were sold to the public. Fashion evolved through the 1950’s, and as it progressed there was no longer a single look that all women attempted to achieve.

The invention of television created different types of women and the first departure from one common acceptable look for women. Women could choose to be anything from a free-spirited tomboy to a glamorous sophisticate. (130)

Thick eyebrows were fashionable during the 1950’s, and brow pencils were used to thicken and define them. Brow pencils were also used to define lips, as lip liner had not become available yet. Mascara and rogue are commonly used, eyeliner was used to extend the eye line, and ‘bow’ shaped lips with defined points on the top were fashionable in red or pink colors.

Much like the 1920s, the 1960’s saw a wave of social change. The opposition to the Vietnam war, the Civil Rights Movement, access to legal abortion and the pill, Rock and Roll, the Kennedy Presidency, the Cold War, and space exploration were all cultural factors that helped shape the trends of the 1960’s.

False lashes, fake hair-pieces, pink and peach lip colors, early bronzer powders, cream eye shadow in tubes, and body makeup came into fashion. Rouge is renamed to blush; foundations come in a variety of colors so matching skin tones became easier, eyebrows are left natural, and all the attention of the face was drawn to the eyes.

False lashes are placed on the top and bottom lashes, sometimes using several pairs on the top lash. They are coated with brown-black mascara. Later on in the decade, British model Twiggy influenced the look of lower lashes that are drawn on the skin with black pencil. (146)

The 1970’s saw the rise of feminism, and with it came an empowered natural woman who exercised, dieted, and sunbathed. Fashion trends were not confined to what came out of Paris, and individuality and self-style was prized. Makeup formulas evolved to be smoother, and botanical essences or ‘naturally derived’ cosmetics were popular. Flat-ironed hair, afros, and bobbed hair were associated with the 1970’s. Along with the promotion of individuality, the development of punk music and style rocked the 70’s. Neon colored hair, spiked Mohawks, provocative clothing, and heavy makeup was all associated with the punk music movement.

Makeup trends in the 1970’s followed the natural look. Sheer foundations were worn, and pink blushes and bronzers were applied from the cheeks into the hairline above the ears. Pink or light brown lip colors were popular on the market, and eye shadow also followed a neutral palette of light browns and peaches. Unlike the 1960s, mascara was worn lightly and did not over pronounce the eye.

If the 1970s was the era of natural, Hernandez categorized the 1980’s as ‘An Era of Excess’. Colors in fashion and makeup were bold and bright, hairstyles were bigger, and femininity was reinstalled with an era of women gaining power in the workforce.

Between the last days of the carefree disco movement and a new generation of a r ising female work force, a woman’s makeup look tended to be heavy and extreme. She became polished, put together, and powerful. Eighties makeup minimized flaws and accentuated a woman’s feminine features with bright blasts of color. (165)

Influence to culture came from all avenues of the media. Celebrities such as rock stars, models, movie stars, and fashion icons all created a variety of beauty movements. From the outlandish punk inspired looks of Madonna and Cyndi Lauper, to the athletic and tanned look of supermodels, women had access to a variety of health treatments, cosmetics, and surgical procedures to keep up with modern beauty demands.

Mascara and eye shadows come in a variety of colors (especially blue), blush and lipstick are in bold pink and red, and concealer in a tube was now available to the public. The modern woman of the 1980’s wore makeup as brash as war paint, but also demanded new formulas and improvements to makeup. Anti-aging remedies began to be advertised with makeup products, such as anti-wrinkle foundation.

Where the 1980’s was audacious in it’s color scheme, the 1990’s subdued makeup, hair, and fashion to a refined and smooth look. It was the era of Starbucks, Bill Clinton, ‘Friends’, and grunge music. Thrift store shopping, the revival of swing-era clothing, and sportswear were commonly seen. Style icons of the mainstream were Jennifer Aniston, Meg Ryan, and Winona Ryder. Raves and grunge music inspired unpolished looks of smeared makeup, multiple piercings and tattoos began to be an acceptable norm, and those straying from the preppy look preferred cargo jeans and flannel. Skinny ‘heroin chic’ models like Kate Moss replaced the once Amazonian models of the 80’s.

Youth and beauty were still prized as trends such as yoga, collagen injections, micro-dermabrasion, cellulite treatments, and a variety of diets appeared. Tan skin was fashionable, as was matte polished face was achieved with foundation and light blush, and natural shades of lipstick and unshaped eyebrows were desirable.

The neutral look of makeup prevails even though women are using more makeup to create a polished and well-defined face. (181)

When Gabriela Hernandez begins the chapter on the 2000’s, the media generation, she goes on to describe how the rise of our Internet use and the spread of knowledge revolutionize beauty trends. Eco-friendly movements and global awareness makes the public conscientious of makeup ingredients and beauty regiments. Reality TV and pop culture icons lead the way for beauty trends and fashion, but they are not corralled by a specific ideal or look. Makeup artists are now celebrities, names like Sephora and L’Occitane are household names, luxury cosmetics rise in popularity, tanning and eyebrow threading are still prevalent, and cosmetic surgery and botox are still commonplace due to media influences.

With information available to the masses, individuals now have more choices in terms of makeup variety and styles ever before. Mineral cosmetics, designer cosmetics, or pharmacy brand makeup is readily available to the contemporary woman. The trends of the Google generation are ever changing and individualistic, as Hernandez names icons like Amy Winehouse, Katy Perry, and Beyonce represent ideals of beauty to different women. The present generation of makeup and cosmetic trends cannot be so easily defined, as new technologies and spread of ideas further redefines our concept of beauty.

The last few pages of the book are dedicated to historical timelines of popular cosmetics and treatments from the 1920’s to the 2000’s. In Hernandez’s conclusion in ‘Classic Beauty’, she leaves the reader with the advice that makeup is representational of an image or identity you want to share with the world, but it doesn’t define you as a person. She hopes that the history, visuals, and information in her book helps the reader develop their own personal sense of style, and to know that they are not locked into the confines of a specific beauty standard. After all, history shows us that nothing – including beauty, is consistent.

Take time to know yourself, adapt fashion into your lifestyle, and celebrate your best qualities. Be curious, love life, and discover something new everyday. There are the keys to ultimate happiness and beauty. (218)

Citations from:

Hernandez, Gabriela. Classic Beauty, The History Of Makeup. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd, 2013. Print.